|

| bron |

|

| Vele handen klik |

29 October 2015

BBC Magazine

Up until the late 1960s the UK sent

|

| bron |

In the winter of 1949, 13-year-old Pamela Smedley boarded a ship to Australia with 27 other girls. She had been told by the nuns from the Catholic home she lived in that she was going on a day-trip. In reality, she was being shipped out to an orphanage in Adelaide and wouldn't see England again for more than three decades.

"We thought it would be like going to Scarborough for the day because we were so innocent and naive," says Pamela, who is now in her 70s and still lives in Adelaide.

"The nuns said that in Australia you could pick the oranges off the trees, and I was very excited because I loved oranges."

Pamela's unmarried Catholic mother had been pressured to give her up as a baby and so she was sent to live under the care of nuns at Nazareth House in Middlesbrough, Teesside.

The place was cruel and joyless, according to Pamela, and she remembers that when the Reverend Mother asked who wanted to go to Australia, every girl in the home put their hand up.

The place was cruel and joyless, according to Pamela, and she remembers that when the Reverend Mother asked who wanted to go to Australia, every girl in the home put their hand up.

Once the SS Ormonde set sail for its six-week voyage, the girls soon realised this would be no day-trip. Instead they were allowed to believe there would be families waiting to adopt them.

"We arrived wearing our winter coats and hats and I remember being hit by this stinking 100-degree heat," recalls Pamela. "I hated it and when we found out we had travelled 10,000 miles just to be put in another orphanage we all just cried and cried."

Pamela would spend the next two years at the Sisters of Mercy Goodwood Orphanage, an imposing redbrick Catholic institution, home to about 100 children.

She was one of as many as 100,000 British children to be sent overseas to Canada, Australia and other Commonwealth countries as child migrants between 1869 and 1970.

Run by a partnership of charities, churches and governments, the schemes

were sold as an opportunity for a better life for children from impoverished backgrounds and broken homes. In reality, an isolated and brutal childhood awaited many of them.

were sold as an opportunity for a better life for children from impoverished backgrounds and broken homes. In reality, an isolated and brutal childhood awaited many of them.

were sold as an opportunity for a better life for children from impoverished backgrounds and broken homes. In reality, an isolated and brutal childhood awaited many of them.

were sold as an opportunity for a better life for children from impoverished backgrounds and broken homes. In reality, an isolated and brutal childhood awaited many of them.

Pamela was one of an estimated 7,000 children to go to Australia, some as young as four. They were often given the false status of "orphans" to simplify proceedings - and most never saw their homes, or their families again.

"Child migrants were actively solicited in Australia as a way of building up the white Anglo-Saxon population and to give the growing economy there a boost," explains Gordon Lynch, Michael Ramsey Professor of Modern Theology at the University of Kent.

"Child migrants were actively solicited in Australia as a way of building up the white Anglo-Saxon population and to give the growing economy there a boost," explains Gordon Lynch, Michael Ramsey Professor of Modern Theology at the University of Kent.

This was not something which happened under the radar - the vast majority of children were sent to Australia with government funding.

"It is sometimes easy to assume childcare continuously improves and becomes more enlightened, but by the time Pamela went out [to Australia] the child migration schemes were really running against the grain of accepted childcare practice in post-war Britain," explains Lynch, who is also a contributing curator to a new exhibition around the subject at the V&A Museum of Childhood in London.

Upon arrival at Goodwood, all the children's personal mementos - photographs, letters, toys - were taken from them and they were left with just a Bible. Everyone was terrified of the Reverend Mother, even the other nuns, says Pamela. She recalls the big strap the nun had around her waist which her rosaries would hang from.

"It is what she'd use to beat us - at night she would walk up and down the dormitories and if you so much as twitched in your bed you'd get the strap."

When she arrived, Pamela remembers defiantly shouting out "God Bless England!" during morning prayers, rather than saluting Australia, for which she received "the thrashing of her life" from the Reverend Mother. Eventually, the nun retired and was replaced with someone much kinder and more progressive, according to Pamela.

Daily life at Goodwood consisted of early prayers, chores and then school, followed by more chores, prayers and an early bedtime of 6pm.

A few hours a day would be spent making the strings butchers use to hang their meat. "It was very coarse string and it made our fingers bleed," says Pamela. "If you did anything wrong the penalty was an extra 100 strings and the nun in charge would hit us with her walking stick."

Child labour helped schemes like the one at Goodwood to be financially viable, according to Lynch.

"It would often be presented as an opportunity for children to learn useful skills or a trade but it was much more about providing some economic contribution," he explains.

Pamela also remembers working in the laundry room and would spend school holidays living with a family and being worked hard throughout her stay. "The two daughters in the family were very good to me but their mother just saw me as free labour," she explains.

Pamela says that every now and then a priest would come to check up on how the children were getting on. "The nuns would stand right beside us when we were asked questions and toys would appear in time for his inspections, but as soon as he left they were taken away," she says.

One of the biggest failings of these schemes was that staff were often poorly trained and poorly resourced and very few follow-up checks were made, explains Lynch. Eventually, the Ross Report came out in 1956, as the result of a visit to Australia by a British team of inspectors, commissioned by the Home Office.

"It made grim reading and said that children who'd already had disruptive backgrounds and been subjected to traumatic experience in the UK were really the last people who should be sent overseas," says Lynch. Confidential appendices, containing the worst of the findings, were not publicly released until 1983.

But despite the report, children continued to be shipped overseas. According to Lynch, the reality became "an uneasy truth" - the Home Office weren't prepared to publicly go against the Commonwealth Relations Office (who were in charge of the schemes) so they tried to discourage local authorities from continuing to send children overseas instead.

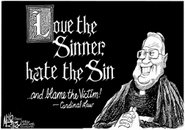

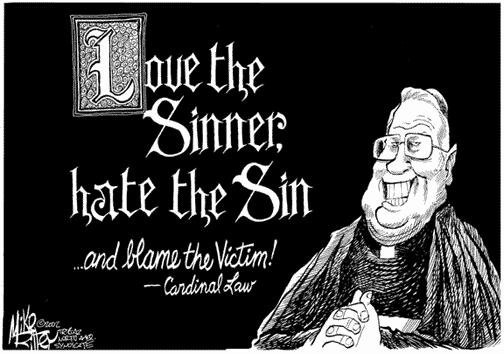

"Furthering the British Empire was still very much a priority and there was also a fear of going up against not only the Australian government, but the Catholic Church," he explains.

The Australian government soon countered the Ross Report with its own glowing review of all the homes under criticism.

Sexual abuse was a harsh reality for many of the children under the care of these schemes, including Pamela, who was assaulted while on the voyage over to Australia and while working at an isolated shearing station, aged 15.

"We were taught never to let a man touch you - and that was all I knew, so I believed I was a sinner and would go to hell for it," she says. When it happened for the first time on the boat, the nuns in Pamela's charge insisted she was just dreaming. "I was terrified and I still go to sleep with my hands guarding between my legs," she says.

At the shearing station Pamela had just one weekend off every six weeks and spent her entire first pay on a ceramic miniature English house. "I bought it to remind me of England," she says.

Desperate to break free of the scheme's clutches, she got married three days after her 18th birthday. In 1989 she was connected with the Child Migrants Trust, who helped her to be reunited with her mother Betty. For 40 years Betty had believed Pamela was adopted by a loving family in England.

|

| Henk Heithuis |

|

| bron |

"I still have nightmares about what happened but hearing the apology gave me a little bit of peace," says Pamela. "It showed that finally somebody cared about what happened to us."

On Their Own: Britain's Child Migrants is at the V&A Museum of Childhood until 12 June 2016

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten