Da's nou toch nog 'ns een een fascinerende omdraaing van de argumentatie van die zoals die elders gebruikt werd: abuses students were not the only victims...

En de onderstreping van de rol van de samenleving.

Moge menigeen waaronder de Stichting Echo en aan die voormalige RK Universiteit Nijmegen , inclusief de HaHa's als Peter Nissen, zich in diepe schaamte hullen!

Wiens brood men eet.....

Catholic bishops to support commission on residential schools

BILL CURRY

Globe and Mail Update

January 29, 2008

Ottawa — Catholic bishops pledged their support yesterday for a truth commission on Indian residential schools, saying Catholics will speak publicly at the hearings to “balance” the official history of what happened for decades behind closed doors.

Participation from the Catholic Church, which ran about 70 per cent of the schools jointly with the federal government, was far from certain until now.

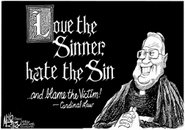

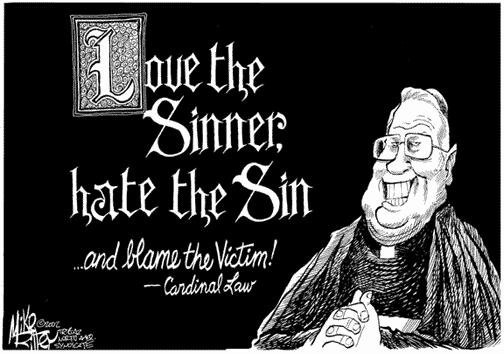

Sylvain Lavoie, the Archbishop of the Keewatin-Le Pas diocese spanning northern Saskatchewan and Manitoba, said the public will learn that abused students were not the only victims in the federal schools policy that lasted more than 100 years.

“There was a lot of good intentions,” the Archbishop said.

“And sometimes the very people staffing the schools were perhaps in some ways victims themselves of a flawed system – of unreal expectations and certainly perhaps very unjust working hours. … I think we'll be able to tell the full story, which I think Canada needs to hear.”

Archbishop Lavoie, who speaks Cree and has spent most of his career working in northern native communities, said all stories should be told.

“That those who maybe suffered in some way, abused, that they would be heard. But also that those who were involved in the schools as teachers or religious, would also be heard,” he said.

Archbishop Lavoie was one of seven northern Canadian bishops who met yesterday morning at an Ottawa church with Phil Fontaine, head of the Assembly of First Nations.

Mr. Fontaine, who has been travelling the country trying to get the 17 distinct Catholic entities to co-operate with the truth commission, praised the bishops for clearing up the “uncertainty” surrounding their participation. However, the northern bishops insisted they could not speak for all other dioceses.

A Truth and Reconciliation Commission is part of last year's multibillion dollar out-of-court settlement between former students, the churches and Ottawa. The commissioners are expected to be announced shortly and will then have a five year mandate to tour the country and compile the official history of Indian residential schools in Canada.

In advance, a cross-country tour to religious communities by the AFN and church leaders is being planned to raise awareness of the commission.

Mr. Fontaine attended two Manitoba Catholic Indian residential schools and, in 1990, was one of the first native leaders to go public with allegations of physical and sexual abuse.

In the years since, many former students have come forward. But what is rarely heard is the perspective of those who worked at the dormitory schools – either as religious leaders, teachers or general staff.

Archbishop Lavoie was asked yesterday whether any effort was being made to approach those accused of abuse to come forward with their stories.

“We really can't say too much about that,” he replied. “Many of them have passed on. So I would think those who wish to speak, would have to speak for themselves.”

Following his informal press conference with the Archbishop, Mr. Fontaine said the biggest victory resulting from yesterday's meeting may be through access to the Catholic records relating to the schools, which could be a key source of information.

“In our view, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission is the most important part of the settlement agreement,” he said. “It's really about writing the missing chapter in Canadian history.”

Revealing New Layers of Dark History

Residential-School Victims Will Gain Access to Stories of Alleged Abusers

By Bill CurryGlobe and Mail

2 January 2007

The painful, personal stories of Canada's residential schools will soon include the perspective of the alleged abusers, as teachers' private journals and thousands of other documents held by churches are gathered and released for the first time.

The massive exercise is part of a five-year project to document one of the darkest chapters in Canadian history.

Called a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the $60-million project is a key, but mostly overlooked, aspect of Ottawa's residential-schools agreement. The $1.9-billion settlement was officially approved by the courts last month.

The project bears the same name as the six-year commission led by former Anglican archbishop Desmond Tutu in South Africa, where people of all races shared searing personal stories of violence and racism during the country's apartheid past.

The purpose of Canada's exercise is to give former students a formal opportunity to tell their stories and to create a final report that will be Canada's official historical record of the period.

But while the report will focus on the broad perspective, many natives will also want to access the papers and photos to learn about their own experiences and family history, said Phil Fontaine, national chief of the Assembly of First Nations, himself a victim of residential-school abuse.

Seeing the meticulous church records will be an important new part of the story, he said.

"We will learn what transpired on a daily basis -- because the officials kept daily journals -- and come to understand how they viewed these schools, the children that they were responsible for," Mr. Fontaine said. "This is an important missing piece at the moment. Because all we've heard is the stories of the survivors, and this is just now coming out. But we haven't heard from the churches."

Amid widespread claims by former students of physical and sexual abuse, the process presents the possibility that victims could look up the diaries of their abusers.

A statement of principles in the terms of reference states that the commission must "do no harm" and that all involvement must be voluntary, but the process is sure to be difficult for many who take part.

Mr. Fontaine conceded that the process will be painful at times, but he said it will ultimately help natives move on and allow all Canadians to understand the impact residential schools had on native society.

"We have to be prepared to expose the ugly truth of the residential-schools experience because that's part of the healing and reconciliation that has to occur. We know that it's been traumatic for survivors . . . this is not easy because we're dealing with painful experiences. But it's all very important. This is not about causing further harm to individuals. It's really about making things better and fixing things and making sure people understand this experience in a way that will enable us to turn the page.

"Three commissioners will be named to hear from former students and teachers and comb through the historical records currently archived by churches and governments.

The records include thousands of photographs, student profiles, reports by visiting church officials and teachers' personal journals.

Residential schools were originally an extension of the missionary work of European religious settlers who sought to convert aboriginals to Christianity. The federal government became involved in joint ventures with the churches in 1874 and took over the schools completely in 1969. The last residential school closed in 1996.

While specific lawsuits dealing with sexual and physical abuse continue, the $1.9-billion settlement recognizes that all students suffered through loss of culture and language and by being forcibly removed from their homes to live at the schools.

Although the commission will have access to any records it wishes, meetings are under way to determine the level of access extended to individual survivors.

Public release of the records will be subject to the federal access-to-information and privacy laws, meaning that individuals named in the documents will likely have to be consulted. Library and Archives Canada will be closely involved in the effort, but the undertaking is clearly daunting for those in charge of the records.

Nancy Hurn, the national archivist for the Anglican Church, manages the church's records with the help of one part-time assistant.

The church is willing to share whatever is needed, she said, but she is concerned about meeting the volume of requests that are likely to flood her desk. The commission's terms of reference says a report on "historic findings and recommendations" must be produced within the first two years.

"I think that is the one thing in the agreement that gives me concern. One is the timing and the other is how the [access and privacy] legislation is going to be applied," she said. "We're doing everything we can to make them available."

Abonneren op:

Reacties posten (Atom)

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten