The Irish Times Vieuw

11-3-2017

It has been a harrowing week. The images that haunt us are of the bodies of hundreds of babies and toddlers buried in a dishonoured grave in the mother and baby home in Tuam , of “Grace” and other children with disabilities suffering years of abuse in a so-called foster home in the southeast, of three beautiful little children and a young mother consumed in an accidental blaze at a facility for victims of domestic violence in Dublin.Each of these stories is distressing enough in itself. Coming at the same time, though, they are even more disturbing. For they strip away a layer of illusion with which we have comforted ourselves when confronted with dark truths about our society's appalling treatment of vulnerable and marginalised children: that was then, this is now. We can no longer assure ourselves that all the horror is in the past and that we live in an entirely new Ireland.

In some respects, we have no right to be shocked by the Tuam story. It is, of course, appalling to think of all of those lovely human beings who did not matter enough during their short lives to be given proper care and who did not matter enough in death to be given a decent burial, even by a church that pretended to believe that every individual was equal in the sight of God and that every life was sacred. But the mother and baby homes were not a secret, and they were not isolated institutions. On the contrary, they were part of what we must acknowledge as a massive system of coercive confinement to which Irish society consigned its unwanted people, its human set-aside.

An empire of repression

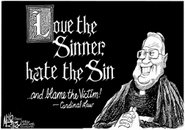

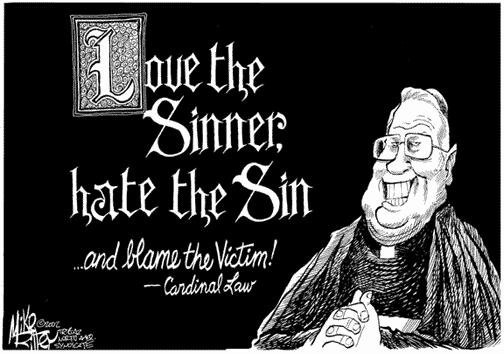

The mother and baby home in Tuam was part of an empire of repression that had highly visible outposts in every major Irish town, encompassing industrial schools, Magdalene laundries and mental hospitals. The Catholic Church bears an enormous responsibility for the systematic cruelty and at times the savage violence of much of this system. It promulgated and imposed a twisted idea of sexuality that used shame as a weapon of power and used women and their children as the living exemplars of that shame. The church has never fully faced up to the consequences of this distortion. That it has contributed just €192 million of the €1.5 billion cost so far of the redress scheme for victims of institutional abuse speaks for itself.

But it is a cop-out to see the church as the only root of all this evil. The mental hospitals that were such a vast aspect of the system of repression were not church-run – and we have yet to have any proper accounting for the awful treatment (and early deaths) of so many people in those dreaded institutions.

The truth is that, in a society where church and state have been so intertwined, cruelty to vulnerable people is a deep stain, not just on religious orders but on politicians, governments, civil servants, communities and families. And it is a stain that has continued to spread. Grace is just one more name we have given to a repeated failure to care for the most vulnerable and to equally cherish all our children.

So how do we as a society face our responsibilities? By honouring the dead and protecting the living. The first part needs to be undertaken with dignity and decorum. The dead must be allowed to rest in peace , which means that we should not embark on a series of mass exhumations at every site where children may have been buried. The need is to identify those places, to name those names, to erect the proper memorials.

But it is also to collect and preserve and digitise archives, so that this story is stitched into our national memory. The work of Catherine Corless in Tuam has set a superb example: the Government should establish a properly funded long-term project in which local communities and professional historians can work together to uncover and acknowledge the truths of this terrible system.

Protecting the living

The second part is to protect the living. We would be the worst kind of hypocrites if we wring our hands over the sins of the past while shrugging off the cruelties and injustices in which we are implicated. We too have our open secrets. We know that children with disabilities are often marginalised and rendered voiceless. We know children in direct provision are often living in conditions harmful to their development and that in Dublin alone there are more than 2,000 homeless children who experience similar or worse conditions. We know that children were first in line for the cutbacks of the austerity years, when consistent child poverty almost doubled. We know that there are nearly a thousand “high priority” children at risk who have not even been assigned a social worker.

After such knowledge, as TS Eliot asked, what forgiveness? We cannot easily forgive previous generations who treated some young lives as disposable. The next generation will not easily forgive us if we continue to repeat this dark pattern.

After such knowledge, as TS Eliot asked, what forgiveness? We cannot easily forgive previous generations who treated some young lives as disposable. The next generation will not easily forgive us if we continue to repeat this dark pattern.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten