The Mayo News

Monday, 24 August 2009 “To paraphrase some words of James Joyce, it is the nightmare from which the Church is trying to awake. I sensed that the Ryan report would be the darkest piece of the jigsaw of abuse and so it has proved.”

Fr Kevin Hegarty

My column this week is a resumé of my contribution to a seminar, ‘The Catholic Church after the Ryan Report’, held during the Humbert summers school in Ballina last Saturday.

Last May, sixty years and one month, almost to the day, after the official declaration of the Irish Republic, at a state ceremony in Dublin, the Ryan report on abuses in our industrial schools was released.

The original proclamation of the Republic in 1949 promised to cherish the children of the nation equally. The cumulative evidence of the report brought graphically home to us the abject failure of the state and its main social and educational agency, the Catholic Church, in their responsibilities to children who were orphaned, abandoned or convicted of petty theft up to the 1970’s.

In a collection of poetry, ‘Flight to Africa’, published in 1963, Austin Clark included a poem called ‘A Simple Tale’.

“A casual labourer, Pat Rourke, who hurried from bricking across the water

With wife and babe, could find no work here.

All slept in a coal hole, heard

(When light, that dwindled through the grating,

Was Wicklowing from strand to hill)

The gulls, loop lines, near Dublin Bay,

Squabble for offal, rut of cur

Or cat around a dustbin, till

A bang in a breadshop, dairy. Brought

To Court, the little screaming boy

And girl were quickly, for the public good,

Committed to Industrial School.

The cost - three pounds a week for each:

Both safely held beyond the reach

Of mother, father. We destroy

Families, bereave the unemployed.

Pity and love are beyond our buoys.”

What we have in the Ryan report is a collection of hundreds of “simple tales”, fused into a compelling compendium of human suffering that is a source of profound shame to the state and the Catholic Church. The report tells the story of an Ireland that was relatively hidden until now. It unveils the geography of a dark hinterland that we failed for so long to name or acknowledge.

Though late in the day for many who endured the system, and much too late for those who have died, it is important that these stories have been recorded. The first step towards any possibility of genuine healing for those, whose childhood days were blighted, is that their experiences are now in the public domain.

Great credit is due to Judge Seán Ryan and his team for their meticulous work over the last decade. The report, drafted in limpid language, has the austere cast of truth. They, and journalists like Mary Raftery, have done the state and the Catholic Church some service.

I expected the Ryan report to be devastating. Since the 1990’s the Catholic Church in Ireland has been hit by a tsunami-like tide of revelations of the sexual, physical and mental abuse of children by clerics and religious. To paraphrase some words of James Joyce, it is the nightmare from which the Church is trying to awake. I sensed that the Ryan report would be the darkest piece of the jigsaw of abuse and so it has proved.

However, I found the report even more devastating than I had envisaged. There were over 800 known abuses in 200 institutions during a period of 35 years.

The adjectives used in the report are stark and brook of no equivocation. Abuse was systemic, pervasive, chronic, arbitrary and endemic. Abuse was not a failure of the system. Abuse was the system.

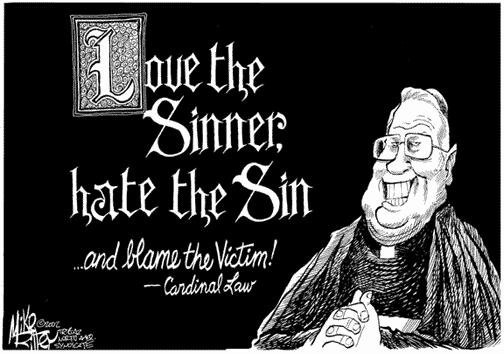

Furthermore, the truth seems to have been extracted reluctantly out of the religious congregations responsible for perpetrating the abuses. The report asserts that, for example, the public apology by the Christian Brothers was “guarded, conditional and unclear” and that “it was not even clear the statement could properly be called an apology”.

Why did all this happen? I am not so arrogant as to believe that I have any or all of the answers but I would like to suggest four pointers; religious authoritarianism; and excessively deferential respect for an authority, that was corrosively non-critical; a cosy clericalism; and an oppressive sexual theology.

In the world described in the Ryan report, loyalty to the Church as institution had a higher value than adherence to the truth. Those who professed loyalty, whether out of fear or a desire to further ecclesiastical ambition, were usually rewarded. Those who tried to speak the truth were rarely listened to and often sidelined.

Where does the Church go from here? One suggestion made at the Humbert School seminar is that church leaders should establish a commission of independent historians, sociologists and theologians to investigate the history, structures, the use of power and the dominant theologies of the Catholic Church in Ireland in the 20th century. In that historical experience lie the reasons for the Church’s present predicament. Hopefully, from such a study, there might emerge proposals for the better governance of the Church, in line with the challenge and charisma of the Christian Gospel.

The Catholic Church in Ireland cannot duck, weave or hide from the implications of the Ryan report. In the words of T S Elliot, after “such knowledge, what forgiveness?”

In his previous post as bishop in Bridgeport, Conn., he let some priests keep working after they were accused of sexual abuse. In closed testimony in a 1997 lawsuit, he expressed doubt about the veracity of most allegations, saying that "very few have even come close to having anyone prove anything." One priest he supported was the Rev. Raymond Pcolka, who had been accused as far back as 1966. Father Pcolka's alleged victims included more than a dozen boys and girls - some as young as 7 - who described being spanked and forced into oral and anal sex. Cardinal Egan kept him on the job until 1992, when another accuser came forward and the priest refused orders to remain at a treatment center. The diocese has since settled lawsuits against Father Pcolka, who refused to answer lawyers' questions during the litigation. Another priest protected by Cardinal Egan was the Rev. Laurence Brett, who had first admitted abuse in 1964 - biting a boy's genitals. After Cardinal Egan became Bridgeport's bishop in the late 1980s, he met Father Brett and endorsed him for continued ministry. "In the course of our conversation," he wrote, "the particulars of his case came out in detail and with grace." Further accusations led to Father Brett's suspension in 1993. In a recent letter to New York parishioners, Cardinal Egan said his policy in Bridgeport was to do a preliminary investigation of accused priests, then send them for psychiatric evaluation and heed doctors' advice. The Connecticut Postlater showed that the policy wasn't followed in the case of the Rev. Walter Coleman, who stayed on the job for more than a year after the Bridgeport diocese concluded in early 1994 that he had abused the son of a woman with whom he had an affair and bought a house. In early June, the pope appointed Cardinal Egan to the Vatican's highest court. In mid-May, the Westchester County district attorney convened a grand jury to investigate New York archdiocesan leaders' handling of sex-abuse allegations.

In his previous post as bishop in Bridgeport, Conn., he let some priests keep working after they were accused of sexual abuse. In closed testimony in a 1997 lawsuit, he expressed doubt about the veracity of most allegations, saying that "very few have even come close to having anyone prove anything." One priest he supported was the Rev. Raymond Pcolka, who had been accused as far back as 1966. Father Pcolka's alleged victims included more than a dozen boys and girls - some as young as 7 - who described being spanked and forced into oral and anal sex. Cardinal Egan kept him on the job until 1992, when another accuser came forward and the priest refused orders to remain at a treatment center. The diocese has since settled lawsuits against Father Pcolka, who refused to answer lawyers' questions during the litigation. Another priest protected by Cardinal Egan was the Rev. Laurence Brett, who had first admitted abuse in 1964 - biting a boy's genitals. After Cardinal Egan became Bridgeport's bishop in the late 1980s, he met Father Brett and endorsed him for continued ministry. "In the course of our conversation," he wrote, "the particulars of his case came out in detail and with grace." Further accusations led to Father Brett's suspension in 1993. In a recent letter to New York parishioners, Cardinal Egan said his policy in Bridgeport was to do a preliminary investigation of accused priests, then send them for psychiatric evaluation and heed doctors' advice. The Connecticut Postlater showed that the policy wasn't followed in the case of the Rev. Walter Coleman, who stayed on the job for more than a year after the Bridgeport diocese concluded in early 1994 that he had abused the son of a woman with whom he had an affair and bought a house. In early June, the pope appointed Cardinal Egan to the Vatican's highest court. In mid-May, the Westchester County district attorney convened a grand jury to investigate New York archdiocesan leaders' handling of sex-abuse allegations.

bron

bron