Hohoho!

Hohoho! Publisher: Crossland Press

Pub. Date: January 2007

ISBN-13: 9780979027994

Sales Rank: 96,864

676pp

En een indrukwekkende recenscie op een vaker verassend en interessant blog .

En dat is, vlak voor de kerstboom, bij een niet zo makkelijk verkrijgbare studie (TIP) van maar liefst haast 700 pagina's natuurlijk nooit weg. En dat op een blog waarvan ook de reacties, alweer, ook interessant zijn.

Net als Podles eigen weblog, orthodox katholiek met een aantal zeer uitgesproken meningen wo over kerk en politiek en zeker over man/vrouw en de op zijn weblog beschikbare artikelen

dat zeker doen.

Hohoho Steeds meer goed nieuws vanaf het groeiend-front-misbruik-'t-is-welletjes-geweest!

It’s not a sin to be angry. This is evident from the scriptural injunction to “Be angry and sin not” (Eph. 4:26), as well as references to God being angry. For Thomas Aquinas, anger is a necessary element of the virtue of fortitude—fortitude isn’t a matter of just putting up with evil, or of enduring sorrow, but includes actively resisting evil, bravery in the struggle, and anger at the evil which has led to sorrow. Summa Theologica, IIa-IIae, Q. 123, Art. 10.

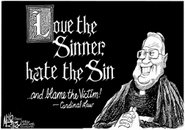

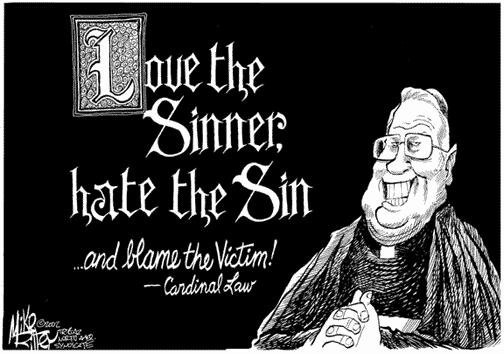

Leon Podles is angry, and wants us to be angry, too. He wants us to be angry at the sin of sexual abuse of children by Catholic clergy. But more than that, he also wants us to be angry at the bishops and pope for not being angry at that same sin. That’s what irks him about this crisis more than anything else—never have the bishops or popes expressed any anger that priests molested kids or that other bishops covered it up and transferred the predators to new hunting grounds.

Podles had done his work well—as I read, I felt a surge of anger at both the system and my own participation in it as a chancery bureaucrat for nine years. I decided I needed to take a breather before writing this review. I wanted to get some perspective.

I read two other books on the sexual abuse crisis, Jason Berry’s 1992 chronicle of the Gilbert Gauthé case in Lafayette, Louisiana, Lead Us Not into Temptation: Catholic Priests and the Sexual Abuse of Children, and Berry’s 2004 book with Gerald Renner, Vows of Silence: The Abuse of Power in the Papacy of John Paul II, which concentrates on the Legion of Christ.

I’m still angry, but I’m now better able to see what is unique about Podles’ book.

These other authors give us great detail about particular epicenters of the crisis and their own journeys as they covered the stories, but Podles’ work stands out as a masterful portrayal of the big picture, linking the stories Berry and Renner reported with stories from other times and places. He paints with broad strokes in places, but gets into some very fine detail in others to help us to grasp the magnitude of some truly horrendous cases. Podles also gives us analysis of the abusers and the victims, and of how each was treated by bishops, and what went wrong.

The bishops are clearly the focal point of his anger:

...

But he goes further, seeing the crisis as about more than the bishops and the priests they coddled: Catholic culture is implicated; specifically a narcissistic clericalism in which the laity, including police and judges and prosecutors colluded.

“The abuse is far more widespread, goes back farther, and is far worse” than has been recognized to date. (9)

A canonized saint tolerated abuse. Rings of abusers go back at least to the

1940s in America, and abuse involved sacrilege, orgies, and probably murder (and

perhaps even worse). Bishops knew about the abuse and sometimes took part in it.Those who complained were ignored or threatened, and the police refused to

investigate crimes committed by clergy. (10)

Podles reveals some of the reasons for his personal connection to the subject, and these revelations give us some insight into how he came to target clericalism. He recounts an experience of physical abuse at the hands of a Christian Brother in high school—”He walked to my desk and slugged me so hard on the face that he broke my glasses.” The teacher went to the principal, and Podles was expelled for having objected to an injustice. This served as a lesson for the boys who remained. But it is also for Podles an example of how the Christian Brothers ruled their schools by intimidation, and he sees what happened to him as one instance of a pattern of physical abuse at Christian Brothers schools extending from Ireland to the US and Canada. Many of these same schools had problems of sexual abuse as well, and Podles sees a clear connection: “An atmosphere of physical abuse had prepared the way for sexual abuse.” The Brothers got the point across that you were to do what they asked without question or complaint. (4-5)

Podles, like many Catholic young men of the period, considered the priesthood; he went to Providence College in Rhode Island, which was run by the Dominicans, and lived in Guzman Hall, a dorm for those considering priesthood. There was an undercurrent of homosexuality there, however, and when a roommate “made a sexually aggressive move” on Podles in his sleep, he fled. (6)

Over the years, he began to wonder about the Catholic Church’s relationship with men. What is it about the Catholic Church—and the priesthood in particular—that attracts such a high percentage of homosexuals and drives off heterosexuals? This question led him to write his 1999 book, The Church Impotent: The Feminization of Christianity:.........

.....“I had been puzzled by the lack of men in Catholic activities, and I was

surprised that my circle of acquaintances included a large number of

homosexuals. I realized that I had met these men through Catholic activities,

through Mass and the charismatic renewal. My research soon revealed that men had stayed away from all the branches of Western Christianity for centuries. Men had doubts about the masculinity of those men who were closely involved with the Church (such as the clergy) and sometimes those doubts were justified. I decided

there was a centuries-old misunderstanding of masculinity and femininity, a

misunderstanding that led men to distance themselves from the Church and that

relegated women to a role of passive obedience.” (7-8; see also pp. 350ff)

The revelations of 2002 should not have caught anyone by surprise. The Gauthé case involved all the same factors of abuse and cover-up, and had brought national attention upon the subject twenty years before. It brought together three unlikely allies, Fr. Thomas Doyle, OP, who was working for the Apostolic Nunciature, Gauthé’s attorney, Ray Mouton, and Fr. Michael Peterson of the St. Luke Institute, who together wrote a report for the US bishops in 1985, “The Problem of Sexual Molestation by Roman Catholic Clergy: Meeting the Problem in a Comprehensive and responsible Manner.” They submitted it to a committee chaired by Bernard Law. They warned of what could happen if the bishops didn’t change their ways. But their report was ignored, Doyle was sent into exile, and the bishops continued doing what they had always been doing.

But the Gauthé case wasn’t the beginning, either. Neither was Davenport. In fact, says Podles, “there is a centuries-old underground in the Church that perpetrates a tradition of abuse,” (68) and this underground is protected and is made possible because of clericalism.

While abuse exists among the laity and outside of Catholicism, among clergy of other denominations as well as scout leaders and teachers, the Catholic crisis is unique. Catholicism makes claims about its priesthood that are made by no other institution (412), exemplified by the statement of Pope Pius XI, “The priest is indeed another Christ, or in some way he is himself a continuation of Christ.” Clericalism is the idea that the clergy really are “the church,” that the role of the laity is to be quiet, give generously, pray faithfully, and, above all, to obey. Clericalism has created a vision of the church where bishops are seen as divinely appointed shepherds whose voice should be heard by both church and state on all issues, spiritual and civil, as evidenced by the plethora of letters on matters such as economics, war, immigration and criminal justice. (416)

Podles sees clericalism as just an institutional variety of narcissism, which is a psychological disorder defined by DSM-IV as a “pervasive pattern of grandiosity (in fantasy or behavior), need for admiration, and lack of empathy.” The narcissist “has a grandiose sense of self-importance,” “believes that he or she is ‘special’ and unique and can only be understood by, or should associate with, other special or high-status people (or institutions),” “has a sense of entitlement, i.e., unreasonable expectations of especially favorable treatment or automatic compliance with his or her expectations,” “is interpersonally exploitative,” and “lacks empathy: is unwilling to recognize or identify with the feelings and needs of others.”

That last point, the lack of empathy, is especially important for considering the reaction of the hierarchy to abuse.

Narcissism pervades Catholic clerical culture, as Podles portrays it. It creates a vision of priesthood characterized by a sense of performance. It leads to a preoccupation with reputation and appearances at all levels (299ff). It requires an audience who adore the performer, lay accomplices who grant clerics deference and privilege. They, in turn, have reacted in anger when bishops have disclosed the faults of their favorite priests and suspended them. The laity also joined the bishops in seeing court cases and newspaper articles as attacks on the church—which is why newspapers didn’t stay with the story after the Gauthé case. (p. 423 ff)The victims were invisible to everyone. The abusers were narcissists

who had no empathy for the sufferings of their victims. The priests,

officials, and bishops of the Davenport diocese were all caught up in a

clerical narcissism, in which only repercussions that affected them had any

meaning. The laity too were afflicted by a Catholic narcissism that idolized

the clergy. (70)

Clericalism also affects the society as a whole, as was seen in the past willingness of cops and judges to overlook the crimes of priests in the belief that bishops were better able to deal with the problem. Even in the wake of the scandals, some defend this system of privilege; Podles points to an article by Michael Orsi, “Bishops Sacrifice Accommodations, Privileges and Rights: Everybody Loses,” Homiletic and Pastoral Review, 2002. (418)

Narcissism isn’t the only psychological disorder affecting priests. Podles summarizes studies done with seminarians and priests over the past six decades indicating that psychological illnesses pervade the priesthood. Already in 1948 William Bier noted that seminarians were more likely to answer questions as women generally did. A 1968 study showed that 70% candidates for religious life were “psychosexually immature, exhibiting traits of heterosexual retardation, confusion concerning sexual role, fear of sexuality, effeminacy and potentially homosexual dispositions.” (93) A 1972 report by Eugene Kennedy said priests tended to have the emotional maturity of adolescents, and not only had sexual difficulties but problems relating to adults. (94) A 1971 study by Conrad Baars found that 60-70% of priests were emotionally immature, and as many as 25% of priests had “serious psychiatric difficulties.” In particular, they did not properly understand the role of human emotions. (95)

...........

If they read Podles’ book, maybe they might begin to understand why people are angry. Maybe then, things might change. That’s his hope. I can’t share it. I think the narcissism, the clericalism, and the emotionally repressed culture go too deep. How do you change an ancient culture? How do you change people who have been selected because they fit a certain profile and whose basic disposition has been reinforced by training and conditioning?

For me, the narcissism and authoritarianism of the Catholic clericalist system reveals the working of “the mystery of iniquity.” It illustrates how the Catholic system as a whole is corrupted by principles that are contrary to the spirit of Christ. Catholic teaching refers to “structures of sin.”

Podles is not about to abandon the Catholic Church, despite all he has related and concluded. He thinks it can be saved, and proposes a series of reforms. A policy of zero tolerance is essential, he argues, as it not only removes individuals but disrupts networks of abusers. The Vatican must extend it worldwide (495). Canon law must be changed to give bishops authority over all priests in their diocese, religious or diocesan, to hold bishops accountable, and to make it possible for bishops to discipline each other (496). The laity must be more directly involved in governance, and should be consulted in all matters that concern them; parishes and dioceses should be audited annually and the audits made public. He suggests care should be taken in ordaining homosexuals—but he goes further, and advocates the barring of abuse victims from seminary. This may well be his most controversial recommendation, but he sees it is necessary because so many abusers were abused themselves. The cycle of abuse must be ended.

Finally, he calls for a renewed ethic which restores the place of righteous anger and the fear of God. “Righteous anger is a forgotten concept, zeal is condemned as disruptive.” (507) “The bishops fear bad publicity; they need to remember the fear of God, if in fact they believe in Him.” (508)

....

That’s his hope. I can’t share it. I think the narcissism, the clericalism, and the emotionally repressed culture go too deep. How do you change an ancient culture? How do you change people who have been selected because they fit a certain profile and whose basic disposition has been reinforced by training and conditioning?

For me, the narcissism and authoritarianism of the Catholic clericalist system reveals the working of “the mystery of iniquity.” It illustrates how the Catholic system as a whole is corrupted by principles that are contrary to the spirit of Christ. Catholic teaching refers to “structures of sin.”

… [S]in makes men accomplices of one another and causes concupiscence,I’d suggest that the Catholic understanding of the papacy and the episcopacy is just such a “structure of sin”; it is “the expression and effect of personal sins,” especially narcissism. These structures that have developed from human sin, and that in turn perpetuate sin, are now seen as constitutive of the Church for Catholicism. Reformation is not possible without undoing what Catholicism sees as of its esse. This reinforces for me the urgency of the prophetic call, “Come out of her, my people, that you be not partakers of her sin.”

violence, and injustice to reign among them. Sins give rise to social situations

and institutions that are contrary to the divine goodness. “Structures of sin”

are the expression and effect of personal sins. They lead their victims to do

evil in their turn. In an analogous sense, they constitute a “social sin”

(Catechism 1869).

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten