During the Indian Residential School era, a black mark on our society so easily dismissed by too  many, the sole goal — publicly stated — was to “kill the Indian in the child.” But it did better than that.

many, the sole goal — publicly stated — was to “kill the Indian in the child.” But it did better than that.

It killed souls, generations of souls.

Yesterday, in Winnipeg, two years after the federal government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper made its historic apology for the wrongs done to our Native people during a bleak period in history that began in the 1870s and only ended in the 1990s, a panel of three commissioners with the national Truth and Reconciliation Commission began hearing first-hand stories of those abuses.

It has been a long time coming. Too long.

As Indian Affairs Minister Chuck Strahl put it: “People should brace themselves. There’s going to be some horrible stories coming out.”

We can only hope. Stereotyping is easy, and it is easy because stereotyping is shallow and steeped in ignorance.

The “drunken Indian” is one such stereotype, bereft of insight into cause and effect, and therefore easy to rattle off as the reason for so many systemic woes among aboriginals.

Alcoholism in our First Nations communities has been crippling. No one will deny this. But where was it seeded?

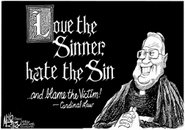

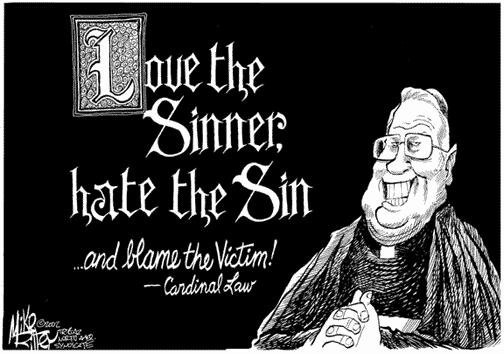

It was seeded, by and large, in the state-financed, church-run residential schools where, over the course of time, some 150,000 First Nations, Metis and Inuit children were separated from their families, most often against their will, and banned from speaking their own languages or following their culture.

Abuse — both physical and sexual — was rampant. If you are raised in such an environment, and such an environment becomes the norm, then it is that norm that is passed on to the next generation.

Fear, guilt and self-loathing are allies of alcoholism. Together they kill souls.

In seven national events over the next five years, beginning in Winnipeg, the true legacy of our residential schools, and the horrors therein, will finally be revealed by first-hand testimonials from those still alive to tell their tale.

Listen, and listen hard.

Hopefully these stories will mute the voices of the racists who believe, for example, that the “drunken Indian” stereotype is a self-inflicted wounding.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Reconcile with that.

many, the sole goal — publicly stated — was to “kill the Indian in the child.” But it did better than that.

many, the sole goal — publicly stated — was to “kill the Indian in the child.” But it did better than that.It killed souls, generations of souls.

Yesterday, in Winnipeg, two years after the federal government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper made its historic apology for the wrongs done to our Native people during a bleak period in history that began in the 1870s and only ended in the 1990s, a panel of three commissioners with the national Truth and Reconciliation Commission began hearing first-hand stories of those abuses.

It has been a long time coming. Too long.

As Indian Affairs Minister Chuck Strahl put it: “People should brace themselves. There’s going to be some horrible stories coming out.”

We can only hope. Stereotyping is easy, and it is easy because stereotyping is shallow and steeped in ignorance.

The “drunken Indian” is one such stereotype, bereft of insight into cause and effect, and therefore easy to rattle off as the reason for so many systemic woes among aboriginals.

Alcoholism in our First Nations communities has been crippling. No one will deny this. But where was it seeded?

It was seeded, by and large, in the state-financed, church-run residential schools where, over the course of time, some 150,000 First Nations, Metis and Inuit children were separated from their families, most often against their will, and banned from speaking their own languages or following their culture.

Abuse — both physical and sexual — was rampant. If you are raised in such an environment, and such an environment becomes the norm, then it is that norm that is passed on to the next generation.

Fear, guilt and self-loathing are allies of alcoholism. Together they kill souls.

In seven national events over the next five years, beginning in Winnipeg, the true legacy of our residential schools, and the horrors therein, will finally be revealed by first-hand testimonials from those still alive to tell their tale.

Listen, and listen hard.

Hopefully these stories will mute the voices of the racists who believe, for example, that the “drunken Indian” stereotype is a self-inflicted wounding.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Reconcile with that.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten