Sunday, May 31, 2009

By Diarmaid Ferriter

Diarmaid Ferriter is professor of modern Irish history at UCD. His new book, Occasions of Sin: Sex and Society in Modern Ireland, will be published in September by Profile Books

In assembling and providing such an overwhelming body of evidence about what went on in residential institutions, the report of the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse has provided a corrective to the atmosphere of secrecy and shame that surrounded these experiences for so many years. It has also provided future historians of 20th century Ireland with invaluable information on attitudes to child welfare.

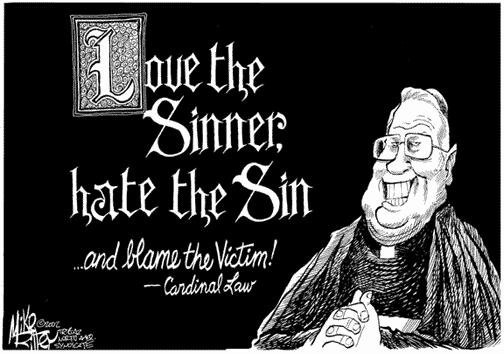

A frequent contention offered by leaders of the religious congregations during the public hearings of the commission was that child abuse in the formative and middle decades of the 20th century was not understood as it is now. They maintained that it was seen primarily as a moral, rather than a criminal, issue and that, given the circumstances of the time, their response was only what could have been expected.

It was also asserted that industrial schools were a positive force in Irish society during difficult times, and that the problems encountered by the religious orders, and their actions, had to be set in the broader context of lackof funding, education and training, and the role of the state as overall manager of the childcare system.

The report of the commission, chaired by Mr Justice Sean Ryan, makes it clear that the extent of the sexual and physical assaults on children cannot be explained away by maintaining that the country was too poor and ignorant. There were much more calculated and sinister forces at work, and a deliberate abdication of state responsibility.

In 2000, a year after the establishment of the commission, archivist and critic Catriona Crowe sought to make sense of the seemingly-insatiable appetite in Ireland and beyond for memoirs of miserable Irish childhoods. She suggested: ‘‘The whole business of untold stories is at the heart of our fascination with these revelations. The private domain of personal experience has always been at odds with the official stories which were sanctioned, permitted and encouraged by the state and the Catholic Church.”

Developing this theme, Crowe suggested that ‘‘these memoirs run like a parallel stream of information alongside the official documentary record, and complement it with their personal immediacy and vibrancy . . . it is the fact that we are hearing a story from the inside of Irish life that gives these books their value as human testimony. The official record can tell us what happened, but rarely what it felt like’’.

Crowe’s observations are also particularly relevant to the voices of the victims contained in the Ryan Report. When giving evidence before the commission in September 2005, one of the Christian Brothers’ leaders, Brother Michael Reynolds, observed: ‘‘I have one group of people saying there was a lot of corporal punishment, and I have documentation saying there wasn’t.”

The obvious conclusion to be drawn from his comments is that the documentation available in the archives of the institutions cannot provide a complete picture. The recounting of the experiences of the inmates of the institutions therefore became crucial in providing the ‘parallel stream’ of information, or what could now be more accurately described as an ocean of grief.

The experiences of the victims, outlined in the report, highlight the underbelly of Irish society from the 1930s to the 1970s. Much of the testimony is bleak and harrowing, and it is difficult to avoid the conclusion after reading these accounts that the greatest blot on 20th century Irish society’s copybook was its treatment of children. The report underlines the huge gulf between the portrayal of Ireland as an unsullied rural idyll, with the bedrock of the institution of the family, and the reality of a Church, state and community that hopelessly failed to create such a society.

It is ironic that such horrendous brutality occurred during what many believed was going to be a century where the concept of children’s rights would be valued and vigorously promoted. Commenting on the introduction of limited legal adoption in Ireland in 1952, Liam Maher, a contributor to the Catholic periodical Irish Monthly, suggested: ‘‘There has been a growing interest in the plight of homeless and unwanted children as the social conscience has become more sensitive towards the unprotected and the underprivileged. This has been called the century of the child.”

This may have been true in theory, but the practice was different. While the Children’s Act of 1908 was regarded as a fundamental step in extending child protection, incorporating in one statute a host of laws and piecemeal legislation that emphasised the social rights of children, it was, in practice, more parent-centred (in the sense of bringing them to account for neglect) than child-centred.

Crucially, it also dictated that ‘‘the courts should be agencies for the rescue, as well as the punishment, of children’’. One of the cruellest aspects of some judges’ decisions was to send children to institutions as far away as possible from their homes, to place even more distance between the children and their parents. It was this 1908 act on which Ireland relied in dealing with the problems of child welfare for the entire 20th century. (A new children’s act was introduced in 2001.)

Once incarcerated, the individual emotional and physical welfare of children was rarely a priority. As a visitation report in relation to Artane Industrial School made clear in 1952, ‘‘the boys are never called on to make decisions for themselves’’. When giving evidence in relation to the minutes of the resident managers of institutions, Brother Reynolds commented: ‘‘Finance, unfortunately, was the main item on the agenda.”

Given the emphasis on the family in Irish life, it might have been thought that this society would be particularly conscious of its responsibilities towards the welfare of children. In this sense, any analysis of child abuse in 20th century Ireland must take cognisance of the interaction of family, Church and state, and the extent to which a crucial part of Catholic social teaching was continually promoted – that the state had no right to interfere with the personal domain of the family when it came to supposedly private issues of health and morality. The Church sought to maintain absolute control over its jealously-guarded areas of interest.

The state that funded the institutions had no intention of disturbing the status quo. An interesting exchange in the Dáil in April 1954 revealed why it would be so difficult to tackle the abuse. This was the result of a query raised by Dublin TD Captain Peadar Cowan, following a call from a constituent, the mother of an inmate of Artane Industrial School. She had been refused permission to see her son in hospital after a 21-year-old Christian Brother had viciously beaten him with a sweeping brush.

Cowan prefaced his query by praising Artane and the Christian Brothers. But he made it clear he wanted an assurance that a person of experience and responsibility would inflict punishment. The then Minister for Education, Sean Moylan, Minister for Education, replied: ‘‘I cannot conceive any deliberate ill treatment of boys by a community motivated by the ideals of its founder. I cannot conceive any sadism emanating from men who were trained to have devotion to a very high purpose.”

The Ryan Commission report will ensure that, in the future, historians of 20th century Ireland can cite the experiences of the victims alongside pious assertions from those who could not, or would not, accept that the institutions they exalted were destroying the lives of many Irish children.

woensdag, juni 03, 2009

Hoe heet de burgemeester van wezel? A world of pain laid bare

Abonneren op:

Reacties posten (Atom)

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten