Executive Summary

01 Physical and emotional abuse and neglect were features of the institutions. Sexual abuse occurred in many of them, particularly boys’ institutions. Schools were run in a severe, regimented manner that imposed unreasonable and oppressive discipline on children and even on staff.

vv 02 The system of large-scale institutionalisation was a response to a nineteenth century social problem, which was outdated and incapable of meeting the needs of individual children. The defects of the system were exacerbated by the way it was operated by the Congregations that owned and managed the schools. This failure led to the institutional abuse of children where their developmental, emotional and educational needs were not met.

v 03 The deferential and submissive attitude of the Department of Education towards the Congregations compromised its ability to carry out its statutory duty of inspection and monitoring of the schools. The Reformatory and Industrial Schools Section of the Department was accorded a low status within the Department and generally saw itself as facilitating the Congregations and the Resident Managers.

vv 04 The capital and financial commitment made by the religious Congregations was a major factor in prolonging the system of institutional care of children in the State. From the mid 1920s in England, smaller more family-like settings were established and they were seen as providing a better standard of care for children in need. In Ireland, however, the Industrial School system thrived.

vv 05 The system of funding through capitation grants led to demands by Managers for children to be committed to Industrial Schools for reasons of economic viability of the institutions.

vv 06 The system of inspection by the Department of Education was fundamentally flawed and incapable of being effective.

v 07 Many witnesses who complained of abuse nevertheless expressed some positive memories: small gestures of kindness were vividly recalled.

vv 08 More kindness and humanity would have gone far to make up for poor standards of care.

v 09 The Rules and Regulations governing the use of corporal punishment were disregarded with the knowledge of the Department of Education.

10 The Reformatory and Industrial Schools depended on rigid control by means of severe corporal punishment and the fear of such punishment.

x 11 A climate of fear, created by pervasive, excessive and arbitrary punishment, permeated most of the institutions and all those run for boys. Children lived with the daily terror of not knowing where the next beating was coming from.

x 12 Children who ran away were subjected to extremely severe punishment.

x 13 Complaints by parents and others made to the Department were not properly investigated.

14 The boys’ schools investigated revealed a pervasive use of severe corporal punishment.

x 15 There was little variation in the use of physical beating from region to region, from decade to decade, or from Congregation to Congregation.

vv 16 Corporal punishment in girls’ schools was pervasive, severe, arbitrary and unpredictable and this led to a climate of fear amongst the children.

x 17 Corporal punishment was often administered in a way calculated to increase anguish and humiliation for girls.

18 Sexual abuse was endemic in boys’ institutions.

vv The situation in girls’ institutions was different. Although girls were subjected to predatory sexual abuse by male employees or visitors or in outside placements, sexual abuse was not systemic in girls’ schools.

19 It is impossible to determine the full extent of sexual abuse committed in boys’ schools. The schools investigated revealed a substantial level of sexual abuse of boys in care that extended over a range from improper touching and fondling to rape with violence. Perpetrators of abuse were able to operate undetected for long periods at the core of institutions.

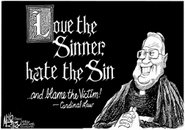

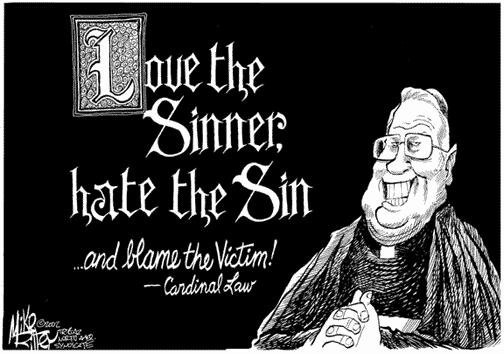

20 Cases of sexual abuse were managed with a view to minimising the risk of public disclosure and consequent damage to the institution and the Congregation. This policy resulted in the protection of the perpetrator. When lay people were discovered to have sexually abused, they were generally reported to the Gardai. When a member of a Congregation was found to be abusing, it was dealt with internally and was not reported to the Gardaí.

21 The recidivist nature of sexual abuse was known to religious authorities.

22 When confronted with evidence of sexual abuse, the response of the religious authorities was to transfer the offender to another location where, in many instances, he was free to abuse again. Permitting an offender to obtain dispensation from vows often enabled him to continue working as a lay teacher.

23 Sexual abuse was known to religious authorities to be a persistent problem in male religious organisations throughout the relevant period.

24 In the exceptional circumstances where opportunities for disclosing abuse arose, the number of sexual abusers identified increased significantly.

25 The Congregational authorities did not listen to or believe people who complained of sexual abuse that occurred in the past, notwithstanding the extensive evidence that emerged from Garda investigations, criminal convictions and witness accounts.

26 In general, male religious Congregations were not prepared to accept their responsibility for the sexual abuse that their members perpetrated.

x 27 Older boys sexually abused younger boys and the system did not offer protection from bullying of this kind.

xv 28 Sexual abuse of girls was generally taken seriously by the Sisters in charge and lay staff were dismissed when their activities were discovered. However, nuns’ attitudes and mores made it difficult for them to deal with such cases candidly and openly and victims of sexual assault felt shame and fear of reporting sexual abuse.

29 Sexual abuse by members of religious Orders was seldom brought to the attention of the Department of Education by religious authorities because of a culture of silence about the issue.

30 The Department of Education dealt inadequately with complaints about sexual abuse. These complaints were generally dismissed or ignored. A full investigation of the extent of the abuse should have been carried out in all cases.

vv 31. Poor standards of physical care were reported by most male and female complainants.

vv 32. Children were frequently hungry and food was inadequate, inedible and badly prepared in many schools.

33. Witnesses recalled being cold because of inadequate clothing, particularly when engaged in outdoor activities.

34. Accommodation was cold, spartan and bleak. Sanitary provision was primitive in most boys’ schools and general hygiene facilities were poor.

xx 35. The Cussen Report recommended in 1936 that Industrial School children should integrated into the community and be educated in outside national schools. Until the late 1960s, this was not done in any of the boys’ schools investigated and in only in a small number of girls’ schools.

xv 36. Where Industrial School children were educated in internal national schools, the standard was consistently poorer than that in outside schools.

vv 37. Academic education was not seen as a priority for industrial school children.

xx 38. Industrial Schools were intended to provide basic industrial training to young people to enable them to take up positions of employment as young adults. In reality, the industrial training afforded by all schools was of a nature that served the needs of the institution rather than the needs of the child.

39. A disturbing element of the evidence before the Commission was the level of emotional abuse that disadvantaged, neglected and abandoned children were subjected to generally by religious and lay staff in institutions.

vv 40. The system as managed by the Congregations made it difficult for individual religious who tried to respond to the emotional needs of the children in their care.

vv 41. Witnessing abuse of co-residents, including seeing other children being beaten or hearing their cries, witnessing the humiliation of siblings and others and being forced to participate in beatings, had a powerful and distressing impact.

vv 42. Separating siblings and restrictions on family contact were profoundly damaging for family relationships. Some children lost their sense of identity and kinship, which was never recovered.

43. The Confidential Committee heard evidence in relation to 161 settings other than Industrial and Reformatory Schools, including primary and second-level schools, Children’s Homes, foster care, hospitals and services for children with special needs, hostels, and other residential settings. The majority of witnesses reported abuse and neglect, in some instances up to the year 2000. Many common features emerged about failures of care and protection of children in all of these institutions and services.

Voorlopige conclussie: In ieder geval De Voorzienigheid werd niet bevolkt door marsvrouwtjes.

vv Zowel ik als anderen zaten kennelijk in een Iers instituut.

vv Het Nederlands ministerie van Justitie mbt de katholieke Zorg zowel als de RK Kinderbescherming was kennelijk onderdeel van de Ierse overheid.

vv Onderzoek o.a. aan nederlandse universiteiten w.o. mbt historische pedagogiek wordt kennelijk belemmerd door het ontbreken van kennis van het Engels resp. Iers.

De Ierse revolutie, waarvan dit staatsonderzoek mbt het residentieel verleden deel uitmaakt, (heeft) het noodzakelijk onderzoek naar, c.q. het nemen van verantwoordelijkheid door Staat én RKK, in overige (W-) Europeese landen ernstig belemmerd c.q. onmogelijk gemaakt!

De Zorg, de noodzakelijke kinderbescherming én (vroegere) tehuisbewoners in overige (W.)Europeese landen zijn hiermee geschaad.

Belastingbetalers in overige (W.) Europeese landen betalen hieraan méér dan hun deel mee.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten